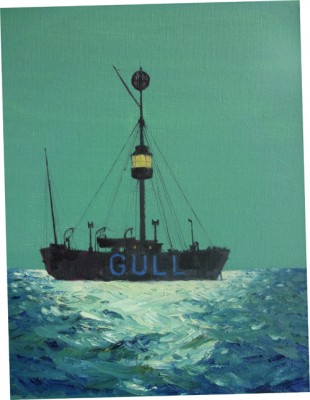

In his book Looming Lights, George Goldsmith Carter describes life aboard a lightvessel guarding the world’s most dangerous sandbank: the Goodwin, maritime grave of thousands of sailors

I reported for duty and found myself aboard a Trinity steamer, which was to put me aboard a ‘fog-ship’, the North Sand Head light vessel, stationed on the Goodwin Sands.

Down river we sailed with a crowd of happy-go-lucky individuals. The Nore, Mouse, Girdler, Mid-Barrow and Tongue lights were relieved, and coals, water, oil, mail and stores delivered. As we stood clear of the mouth of the Thames, around the North Foreland, a freshening north- easter was knocking the sea into a nasty lump. Poking my head down into the soggy pads of my lifebelt I felt thoroughly uncomfortable and miserable, as well I might, being drenched to the skin, and going to a vessel I didn’t know and where I was not known.

At last we were alongside, and made fast. Hook ropes were lowered, coal stores and bed bags were jerked aboard with amazing speed, whilst the motor boat laboured and wallowed, throwing up solid sheets of water between herself and the lightship’s side. Empty, the motor boat cast off, and plunged back to the steamer. Locating the fo’c’sle scuttle I dragged all my possessions below, threw off wet clothing and hastily unpacked my drenched food boxes; the contents of which, however, thanks to excellent packing, were quite unharmed.

I then had time to look around. The decks were varnished, and a cooking stove was for’ard. Hooks for hammocks were driven into beams overhead. In the deck were several covers over the holds in which coal and other things were stored. Through the after part of the fo’c’sle deck-head, innocent of hawse pipes, led the riding cable.

‘ When the siren stopped, after ten days continuous blowing, the silence was positively uncanny’

For the first ten days, the foghorn had to be sounded continuously owing to the misty weather. The only warning I had was the hissing of the blow-lamps warming the compression chambers of the engine. Then the frightful yell of the siren burst upon my eardrums, and with it the thump-thump of the engines. Many and many a time had I heard the lightships’ fog sirens from the beach at Aldeburgh, but it had conveyed no conception of this hellish shriek.

One of my shipmates noticed my distress. ‘Don’t worry about the horn too much, buddy, you’ll get used to it!’ Here he stopped as the two blasts from the siren interrupted him. ‘Always let that feller have his say, you’ll save a lot of breath and patience.’ And thus I learned to regulate my conversation to the intervals between the blasts, and rarely was I interrupted, though conversation was usually cut down to a minimum when we were ‘blasting’.

I got very used to the siren. When, after ten days continuous blowing, it stopped, the silence was positively uncanny. I could not sleep for the first night, but lay in my hammock, actually listening to the deathly silence, broken only by the tinkle of the tide against our sides and the clicking of the lantern’s mechanism. Sometimes in the ripple of the tide there is an elusive music, there is elemental music, too, in the rush and roar of the great winds.

Sometimes the links of our cable would jangle musically too. The old lightsmen said it was the ‘crawlies’ – hermit crabs – creeping over the chains. The old-timers were full of odd stories. One told me it was so rough once that when he came down from the ‘moon-box’ – lantern – the ship had gone.

Once when I was lighting the wicks I saw one of the lamps was flaring up and smoking, so I clambered up again. As I stood on the greasy iron plating, my feet slipped and I fell forward jamming my right eye into one of the very hot smoke stacks. I rushed below and plunged my head into a bowl of cold water. I had a huge white ring of blister right around my eye.

One night the glass fell and fell. The temperature fell, too, and there was an uncanny murmur filling the air. Scattered flakes of snow began to fall. Each succeeding squall grew stronger, the snow fell thicker until it blew Force 10 and the snow was thick as guts. Our siren squealed feebly, its wail whipped away by the gale. Huge seas were roaring past. Our ship sat back on her cable, with the crash of a twelve-pounder gun.

Large slabs of frozen snow were constantly trying to obscure our light, and so we took it in turn to climb aloft, clinging on desperately, for the wrath of that blizzard would have torn one from the rigging like a fly. A livid moon shone pallidly through a sudden break in the sky. Instinctively we gazed to the southard and, as if it had been waiting for that instant, a pale green rocket mounted feebly into the blackness and burst into a shower of stars. We fired an answering rocket as an urgent summons to the lifeboat and down in the master’s cabin the radio transmitter was humming as he called up the Coastguard.

Presently the red and green side-lights and stumpy mast of the lifeboat loomed close alongside. We saw the bulky yellow oilskinned forms of her crew, drenched by solid green water. The light flickered over the crimson salt and wind flayed face of the coxswain. We gestured towards the wreck. The lifeboat crashed off into the darkness, and we saw no more of her. We never even heard if the crew of the wrecked vessel were saved, for we had done our work, and had no share in a spectacular rescue.

– Excerpt from the book, Looming Lights by George Carter