…and how to avoid them. James Stevens reveals the classic pilotage mistakes and explains what you need to do to ensure safe inshore navigation

10 classic pilotage mistakes in navigation…

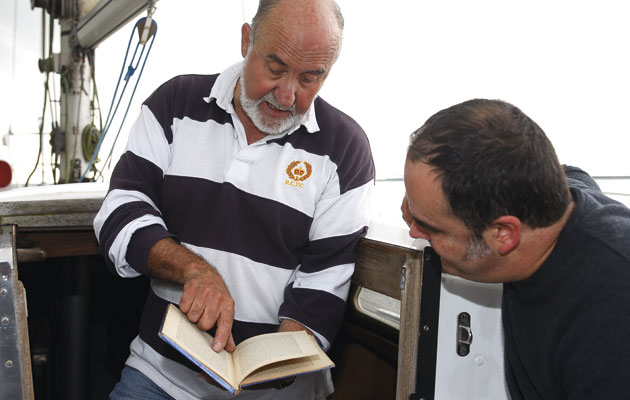

James Stevens, author of the Yachtmaster Handbook, spent 10 of his 23 years at the RYA as Training Manager and Yachtmaster Chief Examiner

With a bit of preparation, hundreds of unlikely ports and rivers all around Britain are navigable and available to small craft. Arriving in these underused and beautiful places is one of the great joys of yachting, but that preparation is pilotage, and it is a very difficult skill to master.

I have yet to meet an experienced skipper – recreational or professional – who has never made a pilotage error. Usually these are pretty minor but each one gives you a slight knot in the stomach with the thought of what might have happened. You can practise boat handling and other techniques until you are so smoothly proficient it becomes second nature, but if you are arriving in a new harbour you must prepare carefully. What you expect to see from looking at the chart isn’t always what you get.

The difficulty with pilotage is relating the information on the chart to the real world. On the chart, navigational features such as buoys are very obvious and so are their light characteristics, but at night against a background of streetlights they can be extremely difficult to find. Add the complication of ships and other yachts and it’s all too easy to get lost even when equipped with every electronic navigation aid.

Good skippers know there are difficulties ahead when entering a complex or busy harbour at night and do the spadework well in advance. You can work out whether the harbour is accessible and the tidal conditions necessary to enter before you leave home.

Over the past 30 years I have examined about 1,500 Yachtmaster and Instructor candidates. During this time I have had the pleasure of watching some masters of the art of pilotage, but I have also seen some pretty spectacular errors. I have been taken into the wrong port, followed leading lights to their logical conclusion ashore and been put aground on numerous mud and sandbanks, but the problems usually start some time before the keel touches the bottom. These are the most common errors, with my advice on how to avoid them.

Essential pilotage kit

While a good deal of pilotage is technique, discipline and the occasional sum, there are a few items of kit without which you’ll struggle. Unless you’re a straight-line day-sailer the chances are you’ll already have this kit aboard but if you don’t, or it’s in such a state that it’s no longer serviceable, you really should get yourself to a chandler and spend some money.

You’ll need a plastic bag for your pilotage plan, a hand bearing compass so you know where you’re headed and binoculars to identify the next mark

Binoculars

A good pilot will be 10 minutes ahead of where the boat is rather than 10 minutes behind, certain of the current position and planning what will happen later on instead of struggling to find out where he is. That means looking a mile or so down the track, to identify buoyage and landmarks, locate transits, look for traffic or white water, and generally satisfy yourself that what’s coming up is what you expect.

It is vital to get hold of a good pair of binoculars. They’ll need well-fixed prisms that won’t dislodge at the slightest impact leaving you with double vision, and which are coated for clarity and light transmission. They should also come with a neck strap and a rubber coating so that they stay out of harm’s way. A decent pair, with a built-in compass, won’t be cheap, £400-500, but they’ll last you a lifetime.

Hand-bearing compass

Whatever the reason – flat battery, loose connection, screen cracked by an errant winch handle – you could find yourself closing your destination without your chartplotter at a moment’s notice. That doesn’t mean you’re lost because you’re surrounded by fixed features, identifiable day or night, on which you can take bearings and triangulate your position. That’s a measure of the import of this bit of kit but for a typical pilotage situation, a hand-bearing compass allows you to look in the right place for the next physical mark you expect to pass.

There are plenty on the market and none is terribly expensive, £50 is plenty. Again, look for a rubber coating and a neck strap, decent damping so you’re not waiting for a minute for the compass card to stop spinning, and ideally a photo-luminescent compass card so that it is easy to use at night.

Rainproof transparent bags

A skipper who’s cracked pilotage will be well-prepared and happy to stand by the helm advising on upcoming course changes, issuing crew instructions and managing sail trim – it should all be done from the cockpit rather than wearing out the companionway endlessly checking. To protect your pilotage plan, chart and pilot book, you’ll need them to hand, in the cockpit, and that means they need protecting against bad weather. Transparent rainproof bags cost a few pence from an office stationer and protect charts and books that cost hundreds of times more.

Mistake 1: Not making a pilotage plan

A pilotage plan with ranges and bearings from one fixed point to another will ensure that you stay on track

Some harbours look so simple that a pilotage plan seems hardly necessary. Southampton Water is a good example. What could be simpler? A near-straight stretch of water with a well marked shipping channel in the middle going directly to the city. On the chart the lateral buoys look like street lamps either side. By day it is pretty straightforward, but by night those well-charted buoys have a backdrop of the city streetlights ahead and one of Europe’s biggest oil refineries on the port side. Some of the buoys are two miles apart, notably Hook and Greenland. If you arrive at Hook and are hoping to find Greenland in the dark without knowing where or what to look for, you could easily end up selecting the nearest green, which takes you up the Hamble. Surely not? Well, I’ve seen it happen.

Best practice

Ensure you have a detailed pilotage plan with the bearing and distance to the next mark from each known position. The aim is to keep the navigator about 10 minutes ahead of the yacht rather than 10 minutes behind. Also, having a plan in hand means that you won’t have to run up and down to check the chart all the time. If the yacht is under sail, the skipper will need to be on deck to supervise the sail trim at each course change.

As the boat approaches Hook the navigator is on deck looking along a bearing of 322 degrees for an Isophase Green 2 seconds light. The boat is put on to this heading and the buoy should be ahead. An entry to a more complex harbour such as Poole needs careful planning by day or night. It is a huge expanse of water with several channels of different depths, separated by hidden mud banks. Finding the buoys in the daylight is hard enough, so it is essential that your plan has every change of course.

Mistake 2: Losing track of the buoys

Instead of working through a list of identifiable marks, each with range and bearing to the next, a skipper who’s not entirely on top of his pilotage often sees what he wants to see rather than what is actually there. It is this lack of planning that leads to a yacht grounding on the Winner Bank in Chichester Harbour almost every bank holiday. Three green buoys guard the north-west side of this bank and they are all well marked on the chart. On a busy and sunny weekend it is all too easy, especially when coming from the east on an ebb tide to miss the most northerly buoy, Mid Winner. The bank shoals rapidly on the ebb and if you hit it you are in for a long wait.

Best practice

When entering or leaving harbours check that what you think is the next buoy is in the right place on the right bearing and is the right colour – and that the breakwater really is the breakwater and is not a row of houses. Don’t just rely on the chartplotter, go on deck with the binoculars. If you wish, each buoy can be ticked off on your pilotage plan as you pass it.

Mistake 3: Blundering on when unsure of your position

Sometimes, shifting sands or silting mean authorities need to move buoys. When did you last check for chart updates?

Chartplotters have dramatically improved our knowledge of where we are, but they are only as accurate as their last update. Above the endlessly shifting sands and meandering swashways of the East Coast, an out-of-date chart is a work of fiction, or more accurately a historical document.

There is no substitute for accurate visual pilotage. While the buoyage might be shifted by the harbour authority or Trinity House to mark a channel’s new position, the colour and characteristics usually stay the same. The normal planning principles apply. If you are in doubt, stop – preferably at a known position. A common error is to carry on hoping that it will all become clear. It won’t.

Best practice

If you’re not seeing what you should be seeing, heave-to in your last known location and find out why

The one place that you know is safe is where you have just been afloat – so go back if necessary, being careful not to be offset by the tide. You can then get your bearings and carry on when you are absolutely sure that the mark ahead is the correct one.

Mistake 4: Looking at the screen, not the scene

Every Yachtmaster examiner has watched candidates piloting a yacht from the chart table trying to establish their position while buoys, lighthouses and other blindingly obvious features are passing by unnoticed. GPS is a great tool but it is not a substitute for looking where you are going.

Best practice

The answers don’t always lie on the chart. Look around for something that can help you to locate yourself

Competent skippers need to be on deck at every course change to ensure that the next mark is accurately identified, the helmsman really is on course and the sails are trimmed or the gybe or tack supervised. There is also the problem of avoiding yachts and shipping and other floating hazards such as lobster pots. Calling up instructions from below is not recommended.

Mistake 5: Not making use of the pilot book

A marina at the entrance to the Medina River, Cowes, looks inviting – but you’re not invited. A pilot guide tells you that and tells you why

If you’re coming into an unfamiliar port, chances are you’ll identify yourself as a first-time visitor pretty soon, probably by making a simple error that locals wouldn’t make, such as picking a swell-swept anchorage, mooring where you shouldn’t or using a channel meant for other craft. For instance, on the chart, the Royal Yacht Squadron Haven looks a cosy place to moor, and it is – but not for the public. The same applies to ferry berths and other private moorings. Many harbours colour code their visitors’ moorings. All this is explained in the pilot book – ignore it and you can expect to be disturbed by the rightful owner.

Best practice

Rather than being a chore, I see the pilot book as a way of saving time and effort. Most are a good read, too. The pilot book coupled with the almanac will tell you about hazards on the way in – that awkward sandbank near the fuel dock, where to moor, the cost, the best place to eat and more, including pictures. These aeren’t facts you want to pick up by trial and error. The books are money well spent and give information you cannot obtain any other way.

Mistake 6: Misidentifying lights and day shapes

Most yachtsmen go around the stern of ships, avoiding the possibility that a ship is the give way vessel. This is fine but there is trouble ahead if you cannot identify a tug or a trawler, both of which are hazardous astern.

A surprising number of yachtsmen are vague about terms used on the chart for the characteristics of fixed navigation lights. Iso 10s for example means on for five seconds and off for five. The 10s refers to the total period of the light. This matters in areas such as the Thames Estuary where there are a series of mid- channel buoys marked Iso 5s and Iso 2.5s. With sector lights on lighthouses it is important to be able to answer the question: ‘If I was here at night, what would it look like?’

Best practice

A good reason for taking an RYA course is to knuckle down and actually learn the Collision Regulations rather than promise yourself that you might do it in the future, or rely on finding the right configuration of lights and shapes in the almanac as valuable seconds tick by. An RYA course will also help you fill in those knowledge gaps on your chartwork, and that can save you a great deal of confusion.

Mistake 7: Ignoring the tidal stream

If your wake differs obviously from your heading, your course over ground could be out by 10º or more

Once the crew can see the lights of the destination, they start looking forward to getting ashore. A sure way of dropping morale is to allow the tidal stream to take the yacht downtide of the port, resulting in a long, slow motor or sail back. Equally frustrating and sometimes dangerous is when the yacht is nearing a harbour across the tidal stream and the helm allows the boat to be set sideways instead of following a transit. Ignoring tidal stream in pilotage waters is really hazardous in areas such as the Channel Islands or Scilly where you cannot take your eye off the ball for a minute – which is about the time it takes to find a rock.

Best practice

The transit is a great pilotage tool. It is accurate to a boat width, better than GPS and allows you to remain where you should be – on deck. It does not even have to be on the chart. Providing you have identified your next mark or the harbour entrance, simply line up a shore feature behind it and keep it there.

Mistake 8: Staying in the main shipping lane

A deep draught vessel under way in a narrow channel has right of way – by dint of the Colregs and basic physics

We all have a healthy respect for ships – with very good reason. In spite of this, every ship’s pilot will tell you that some yachtsmen use the main channel in busy ports where there are good safety and legal reasons for not doing so. It is essential to read the Collision Regulations and understand how they apply to large vessels constrained by draught in narrow channels – where yachts should keep clear.

Best practice

If you can, stay out of shipping lanes and channels. The safest place to be is shallow water, where ships can’t get you, even in fog, and ideally to windward to avoid grounding on a lee shore. Piloting a yacht is hard enough without being confronted by a supertanker.

Mistake 9: Ignoring the echosounder

Even the best navigators sometimes drift off the intended track. Knowing the rough depth along your intended path – something you can write into a pilotage plan – means that you are more likely to notice the minute you go off course.

Best practice

Include expected soundings in your pilotage plan and check the sounder regularly to make sure you’re not off course

The echosounder is an essential reference when entering harbour. You must know how it is calibrated and what it will read if you touch the bottom. It is really useful if you venture into areas where the hydrographer hasn’t really tried too hard, such as the upper reaches of rivers. A good example is Fowey, where you have to feel your way up the river by zig-zagging along contours using read-outs from the echo sounder alongside the chart. The reward is a pass into some of the most beautiful parts of Britain.

Mistake 10: Grounding at low water

I resolved to learn how to do this calculation while leaning over at 45° in the Treguier river. Fortunately we came upright on the flood without damage but it was a miserable night. Before taking a Yachtmaster exam it is worth looking at the likely harbours you will visit and their tidal data.

Best practice

If you intend berthing in shallow water you have to know whether you will ground at low tide and you should know this before you stop. It is probably more important than any other tidal height calculation. In most places a huge degree of accuracy is not required so your skill at wrestling with secondary tidal height calculations is usually unnecessary.

The nearest half metre is good enough but it is a bit of maths obtained from the almanac or the computer which is essential if you anchor and pretty important on a mooring or even in a marina.

Many yachtsmen become confused about where chart datum fits into the calculation. In fact, the only numbers you will need to avoid going aground are the fall of the tide to the next low water, the draught of the yacht, and a safety margin under the keel. Add these three figures together and check the chart for that depth or somewhere deeper.

Enjoyed reading this?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.