Poled-out genoa, spinnaker or cruising chute? Chris Beeson finds out which to use to sail downwind, when and why

Which is the best way to sail downwind?

Downwind cruising can offer some of the most relaxing sailing of the season. Just ease the mainsheet, pole out the genoa, engage autopilot, mix a drink and let the miles tick away as a cooling breeze rolls across the transom. However, with all that time on your hands, the mind can start to wander.

You might start wondering, if progress is a little slow, whether you would be better off digging the spinnaker out of its home in the forepeak? Would the bothersome cat’s cradle involved in putting it up and the tricky business of gybing, potentially perilous for a couple, pay off in time saved? Or would rolling make life too uncomfortable? Perhaps you have a cruising chute? Would sailing the angles downwind be quicker than a spinnaker running dead downwind, even if it does involve more activity? If you stick with your poled-out genoa, how much longer, if at all, will the trip take?

These are questions that any cruising sailor might ask, but what is the answer? The likelihood of a boat identical to yours sliding past with a different downwind set-up, offering a direct comparison, is seriously remote, and two identical boats with two different set-ups: all but impossible.

How do we find out?

We spoke to Sunsail, which very kindly agreed to loan us three identical Beneteau F40s from its racing fleet in Port Solent. Each boat would be crewed by two, with a third onboard to take pictures and make notes.

Each boat would fly a different downwind rig and sail in the same wind on the same day to settle the issue. The criteria used to select the best downwind rig were speed, comfort and hassle.

The plan was to check wind direction on the day and set a distant waypoint dead downwind. The boats would start in a line, and the distance to waypoint was noted. After sailing downwind for a set period, the distance to waypoint would be noted again to measure how far down the track the boats had got.

On the day, the wind was forecast to back from NW to W, and remain quite light at around 5-10 knots. With a knot of ebb tide under us, the apparent wind would reduce still further. It was also a baking hot day so a sea breeze looked certain to back the little wind we had even more. The upshot was that we noted our start position, our finish position and any course changes, and simply sailed downwind until the answer became obvious.

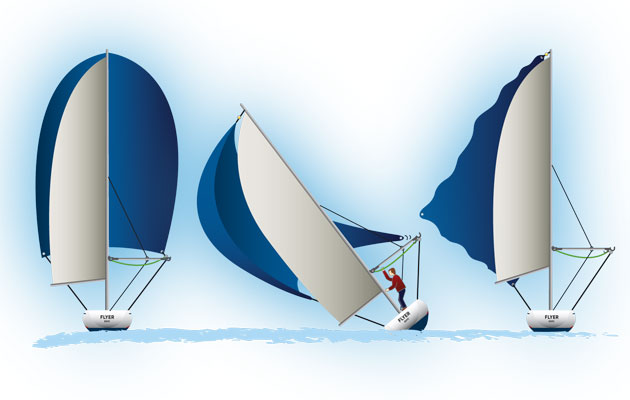

How to avoid the spinnaker death roll

The main peril of sailing downwind in a breeze is rolling. It may start gently but within seconds you can be rolling from rail to rail and a moment later she rolls too far, the rudder loses grip and the boat lays down beam on under a tattoo of angry nylon.

There are a few key ingredients to rolling. Conditions may be gusty, and there’ll likely be too much wind for the sail, which you should have dropped by now. Waves are probably a factor too. If there is too much twist in the main, a side force is generated at the top of the mast that can begin the roll. As she rolls, the spinnaker rolls from side to side and its centre of effort moves much further outboard, exacerbating the situation.

You can always head up a point or two, away from dead downwind, to reduce roll, but if you need to head dead downwind, you can control the situation by using plenty of vang to flatten the mainsail’s leech.

To stop the spinnaker rolling about, ease the pole forward a touch to move its centre of effort closer the centreline, and strap it down by lowering the pole and hauling the tweakers, or ‘twings’, down to deck level, effectively moving the spinnaker sheet’s ‘car’ position forward.

If you do find yourself in the dramatic final act of a death roll, beam on and going sideways with the rail under, just release the spinnaker halyard (this is why it’s important to make sure halyards are always flaked properly). The boat will pop upright and you can start recovering the spinnaker you should have dropped earlier. Clever cruisers will drop the spinnaker early if the wind builds.

If you have a snuffer to tame a spinnaker, great. If you don’t, before you hoist, rig a quick release line from the inboard end of the pole to the guy’s snap shackle. Pull it and the tack releases, leaving the sail to flap in the main’s lee. Just haul in using the lazy guy or sheet.

Before you hoist, rig a quick release line from the inboard end of the pole to the guy’s snap shackle

Poled-out genoa

In many ways this is the default set-up. Most yachts already have a mainsail and a genoa or jib, and if there’s enough breeze, the boat goosewings downwind with the main on one side and the genoa on the other. No extra kit or expense involved, so it’s perfect! Or is it?

The problem with goosewinging is that it’s a fragile set-up. If winds are light, the jib will collapse on the centreline and slat about. This is both slow and expensive, as slatting damages sails. If there is enough breeze to fill the sail, it has lots of depth but what you need is area – a flat sail to catch as much breeze as possible. If there’s plenty of wind but its direction isn’t absolutely stable, or the boat is rolling, again the jib collapses but this time refills with a rig-shaking crack.

The solution is to push the genoa’s clew out so that the foresail is flat and ideally perpendicular to the wind. The sail catches maximum breeze and it can’t collapse. If you’re goose-winging, try prodding the genoa’s clew out with an extended telescopic boathook – see how the sail area increases.

How to set up

There are some in the Yachting Monthly office who have simply stuffed a boathook into the clew and lashed the inboard end to the shroud. Crude perhaps, but it can be effective.

The recommended options are either a whisker pole, usually light weight and telescopic to some extent, or a spinnaker pole. Both attach to the mast inboard and a sheet outboard, up- and downhauls and, ideally, an afterguy to stabilise the pole.

As our Sunsail F40 had a spinnaker pole, we set that up. We decided not to clip the outboard end to a genoa sheet as it hampers any emergency manoeuvre – you can’t tack with a pole on the sheet.

Instead we tied a third sheet, or afterguy, to the clew, ran it back through the pole end (a block lashed to the pole end would chafe less) to a block on the aft quarter, which gave us a better sheeting angle than the genoa sheet cars allowed. This gave the pole three-point stability, and if we needed to head upwind in a hurry, to recover a man overboard perhaps, the sheet could just be cast off and the pole left in place, leaving us in full control of the genoa.

As the wind builds, the unique advantage of this set-up is that you can reef the genoa to reduce sail area. The mainsail will long since have been dropped but you can sail on under headsail alone, taking in a few more rolls as required.

Gybing

This involves a trip forward. We tripped the pole from its port gybe and lowered the outboard end onto the foredeck. Then the third sheet was unreeved, leaving the boat conventionally goosewinged, led through the pole end and back outside the lifelines to the block on the other aft toerail and onto the primary winch. Hoist the pole on the opposite side, gybe the main, haul in on the afterguy, then adjust the pole’s lines until it’s stabilised. All in all, gybing took about five minutes.

How did it go?

We had our spinnaker pole already rigged with the inboard end slotted into the mast cup and the outboard end resting on the pulpit. That was easy, no-nonsense prep. With the afterguy clipped into the end of the pole for a port gybe set, we hauled it and unfurled the genoa until the pole end reached the clew, then strapped the pole down using up- and downhaul and afterguy.

We were off. Well, sort of – we made 3.3 knots over the ground with the wind 3.1 knots apparent. Our problem was, squared right off, we were not generating any apparent wind, or so little as to make no difference. We had only a minimal feel of steerage, but we retained full control and held a good course dead downwind.

At first we made ground over the asymmetric boat by holding a straight course: she had been 50 yards ahead, but by the time she came back on port gybe she was 50 yards astern of us.

Then the wind backed 45 degrees, freshened a touch, and had us sailing east instead of south-east, our advantage evaporated and even though our speed over the ground went up to 5.1 knots, the asymmetric boat was 200 yards ahead of us and the symmetric boat remained a quarter of a mile ahead.

Gybing was a controlled business, not a tremendous ordeal for two, and would have been quicker if we hadn’t rigged the afterguy, but it was the seamanlike thing to do. That aside, we could happily have switched on the autopilot and watched the world go by.

Dropping

This was only slightly more involved than furling a genoa. We released the afterguy, hauled on the furling line and that was that. Then the only thing left to do was to ease the pole uphaul, unreeve the afterguy and lower the inboard end of the pole.

Symmetric spinnaker

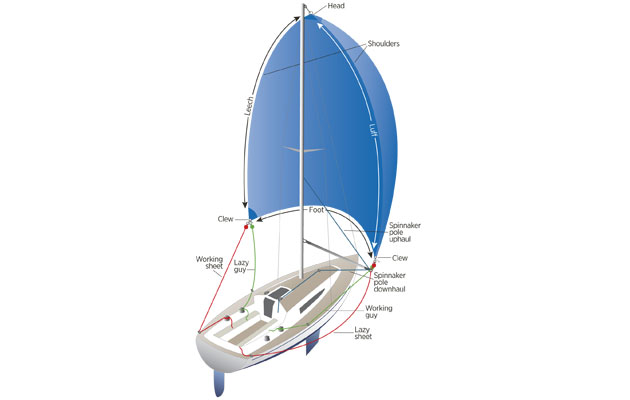

A symmetrical spinnaker is used as both an aerodynamic sail when reaching, with air flowing across it like a foil and creating lift, and also as a windjammer, simply blocking the wind when heading deeper and dead downwind.

There are some issues when using it. In light winds even the slightest gust can accelerate the boat so that she sails through her apparent wind, leaving the spinnaker drooping lifelessly. In these conditions the best option is to head onto a broad reach, so apparent wind, and therefore boatspeed, will be higher. The only problem then is the need to gybe.

Another issue with heading dead downwind under spinnaker is that increases in wind strength can go unheeded. The boat speeds up and everyone has a jolly time, but if there’s a sea running and the boat begins to roll, things can go wrong very quickly. By that point, there’s often enough wind to make going forward to drop the spinnaker an edgy business.

How to set up

This can be a lengthy business for a couple. First, sheets and guys need to be correctly rigged. As well as needing turning blocks in all the right places and the lines themselves, you need to rig the sheets and guys correctly because the loads involved in flying a sail of that size tend to make a big deal of any mistakes. You also need to know that the spinnaker has been packed free of twists, and that the corners you believe to be the clews and the head are indeed just that. Check all this before setting off as it’s easier on a stable boat than at sea.

The next step is to hoist the pole, then the spinnaker. It’s quite a hassle for a crew of two. Ideally, the helmsman would head dead downwind and flip on the autopilot just before the hoist, then move forward in the cockpit.

The foredeck crew hoists the halyard at the mast and the spinnaker goes up sheltered by the mainsail, while the cockpit crew looks after the halyard tail, sheets and guy. It’s much easier if you have a snuffer as the sail would be hoisted to the masthead before it was opened, so you can check everything is as it should be before filling the sail, and, with the halyard hoisted, there’s one less line to look after.

Gybing

The foredeck crew goes forward and the helm runs dead downwind and flips on the autopilot. With both sheets hauled tight and cleated off, the foredeck crew grabs the lazy guy – the helm needs to make sure there’s enough slack in the guy to do this – then trips the pole off the working guy. The helm lowers the pole uphaul so that the foredeck crew can load the new guy, then the helm hauls the pole up on the new gybe and hauls in on the guy, releasing the old sheet and trimming the new one. In benign conditions it’s a relatively straightforward job for the foredeck crew but the helm has five different lines to control in synchrony with the foredeck crew. Get the choreography wrong with a sail of this size in any but the lightest winds and the results can be expensive.

How did it go?

Sailing as a couple, you need a very slick routine to fly and gybe a spinnaker with confidence. The biggest problem is the sheer number of lines required. With a sheet and guy each side you quickly run out of winches, especially if you’re hoisting or dropping the spinnaker behind the jib, as that needs a winch too. Then there’s the need for the spinnaker sheet to ideally be taken across the boat to the opposite halyard winch, so that the trimmer can see the sail. At one point we ended up with two sheets criss-crossing the cockpit!

Had we not been intending to practice a few gybes, we could have got away with sheets alone. In these winds we could have hauled the twings, or sheet barberhaulers, down to the deck to create a new guy after gybing but in anything stronger, twings probably aren’t up to the loads of a guy.

Once flying, a symmetric spinnaker is fairly simple to control downwind, provided you don’t head so deep that the spinnaker backfills as you sail through the apparent wind, and wraps around the forestay.

Dropping

We used the ‘letterbox’ method to drop the spinnaker. It’s the easiest way to drop but you do need a loose-footed main. Feed the lazy guy between the main and boom and get the halyard ready to drop. Ease the pole right forward, give the halyard a turn or two on a winch, hand the tail to the helm, stand in the companionway, release the halyard clutch and start hauling on the lazy guy. The helm eases the halyard enough for the crew to haul the sail in, but not so much that it touches the water.

Cruising chute

A cruising chute, also known as an asymmetric spinnaker, is one that has its tack and clew at different heights. The sail flies from a bowsprit, projecting the sail’s tack beyond the pulpit so that its foot doesn’t foul. As its tack is on the centerline, sailing dead downwind isn’t ideal because the main pretty much blankets the entire sail.

A goosewinged asymmetric can run dead downwind but we decided to use it for the purpose it was designed: sailing the angles. It was a decision forced on us somewhat by the light winds, meaning that the apparent wind often died away when heading dead downwind, collapsing the sail. Sailing the angles gave us more apparent wind, and so more speed.

How to set up

We were inside-gybing, with the dotted sheet, so the clew passed between the chute luff and the forestay. Rig the solid sheet for an outside gybe

We had no bowsprit and the bow roller didn’t project beyond the pulpit so we strapped the spinnaker pole into the bow roller and lashed a block to the end of the pole. We would run the sail’s tackline through this block and lead it back to a halyard winch. We didn’t want to use the pole-end fitting because it wasn’t designed for the perpendicular loadpath the tackline would impose. This arrangement allowed us to project the tack beyond the pulpit. Sheets were run outside the lifelines to blocks on the quarters and back to the primary winches.

Gybing

The beauty of gybing an asymmetric is that it can all be done from the cockpit. There are two ways to gybe an asymmetric: inside (between the luff and the forestay) and outside (outside of both). The latter works well in all but the lightest winds but often, during gybes, the old sheet ends up sliding down the luff and under the bow. That’s why you see asymmetric racing boats with bits of sail batten taped to their bowsprit, or ‘horns’ on the tack: to snag the lazy sheet. That’s not a problem with inside gybing but there is a chance the sail will wrap around the forestay during the gybe if your technique isn’t slick. We opted to inside gybe and from sailing on one gybe to sailing on the other took 10-15 seconds.

How did it go?

With the sailbag clipped to the lifelines, the tackline was attached, sheets run, then the halyard was clipped on. The tackline was hauled in to get the tack over the pulpit to the tackline’s block, and the sheet was loaded on the winch and self-tailer with plenty of slack.

Running almost dead downwind we hoisted the sail easily. With the halyard clutch closed, we came up onto a broad reach, the sail filled and we trimmed on.

The plan had been to broad reach at about 150° to the apparent wind and flip on the autopilot. However, the pressure was so patchy that the apparent wind was constantly shifting, coming forward onto the beam as we accelerated and aft as we slowed. Hand-steering was necessary.

After a laboured first gybe, our technique improved rapidly. As the boat heads down, the old sheet is eased until the clew is just forward of the forestay, then the new one is hauled in. Steer dead downwind until the clew is round the forestay. Watch the clew or mark the sheets so that you know when you’ve eased enough.

As the new sheet is hauled in, come through the wind, bring the main over and come up to fill the sail. In these light winds we gybed by hauling the falls of mainsheet across. In stronger wind, goosewing while sheeting the main onto the centreline before gybing.

Dropping

We headed dead downwind so that the main blanketed the sail. If we had a sock, we would just release the sheet and snuff the sail from the foredeck then release the tackline. With no sock, we gave the spinnaker halyard one or two turns on a winch to stop the sail falling into the water, passed the tail to the helm, released the clutch, hauled down the sail, unclipped the running rigging and bagged the sail.

If your mainsail isn’t loose-footed, don’t haul in the chute under the boom as there’s certain to be a loose split pin that will tear the sail. Sit on the sidedeck, haul the chute into your lap, then feed it down the hatch.

So, which is the best way to sail downwind?

FASTEST: spinnaker

It’s no surprise that this went in order of sail area. The spinnaker (128m2/1,378sq ft) is almost 30% bigger than the cruising chute (93m2/1,001sq ft) and over three times the size of the genoa (37m2/398sq ft). The spinnaker was quickest at every stage – but not by a distance proportionate to sail area.

After 7.1 miles of sailing, the spinnaker was about 400m, or 0.2 miles, ahead of the poled-out genoa, only 3% faster, with the cruising chute just a few metres behind the spinnaker. It was closer than expected but if speed is your priority and you know what you’re doing, choose the spinnaker.

In light winds, the spinnaker and cruising chute boats had to sail the angles to create some apparent wind and fill the sail. The poled-out genoa, though much smaller, was ready to catch the slightest zephyr, and sailed the shortest distance.

The cruising chute boat sailed furthest, gybing eight times to the spinnaker’s three and the genoa’s two. However, on one of our gybes, we found a patch of wind and accelerated away while the spinnaker and genoa boats were stalled. In these conditions, sailing further meant we could find some little patches of wind that the others didn’t.

MOST COMFORTABLE: poled-out genoa

We got none of the rolling that can turn a downwind passage into something of a fairground ride. In a stronger breeze, the genoa boat will roll least because the sails’ centre of effort is lower. In heavier weather, when you’re running under poled-out headsail alone, you can reduce sail area by furling. It’s the only strong-wind option of the three for shorthanded cruising.

Running in light winds the poled-out genoa is always set, whereas the spinnaker hangs, risking a twist

The spinnaker’s centre of effort is higher so it rolls most in stronger winds. There are techniques to limit it and avoid the ‘death roll’ but take them early because once she starts rolling, doing anything except hanging on isn’t easy.

By sailing the angles the cruising chute boat avoids the entire issue of roll as heel will be constant. Speed, and therefore apparent wind, is highest of the three set-ups too. In stronger winds broaching is possible if the boat heels so far that the rudder stalls. In stronger breeze, the greater sail area is a liability.

LEAST HASSLE: Cruising chute

With no pole, it’s easier to manoeuvre quickly and visibility forward is better than the poled-out genoa

Just one sheet to handle instead of six lines for a spinnaker, quick to gybe and no need to go forward

The spinnaker crew was the most hassled. The pole needed rigging, sheets and guys running, and there are lots of little details to get right. We dip-pole gybed but even end-to-end gybes require a spell forward as well as having someone to work the cockpit.

The genoa boat had a relaxed time in between gybes, but again, any gybe involves a trip forward and someone choreographing in the cockpit. Gybing a pole is a hassle, regardless of what’s on the end of it.

Even in light airs, helm and trimmer must be on the ball – fine if you like sailing a boat rather than riding it

The cruising chute boat gybed in seconds without a trip forward. In lighter winds it makes more demands on the helmsman and crew, trimming and changing course to keep the sail filled downwind, but if you enjoy sailing boats rather than riding them, activity on the cruising chute boat is constant but never demanding. On the other boats there’s less to do, except during gybes when there’s too much for two. Visibility forward is decent so, for manoeuvrability in crowded waters, this and its gybing speed give it the edge.

The yacht designer’s view

We spoke to Luke Shingledecker of Farr Yacht Design, the company that designed the Beneteau First 40

‘The best progress downwind is often achieved by sailing the angles because the apparent wind speed is greater, and the apparent wind angle is closer to a reach, where the sails can generate lift and are more efficient. Dead downwind, the sails just catch wind. Sailing higher increases boatspeed enough to overcome the extra distance sailed.

‘In stronger winds, the loss of apparent wind speed is a much smaller portion of the total windspeed so the best progress downwind occurs at deeper angles.

‘Dead downwind, increasing sail area by switching from poled-out jib to spinnaker increases thrust, which increases boatspeed. But increased boatspeed decreases the apparent wind speed, which means less thrust. So, as you found, the increase in boatspeed is much smaller than the increase in area. Also, the thrust required to increase speed is not proportional; at typical boatspeeds, the required thrust increases with the third power of speed (30% more thrust to go 10% faster).

‘Reviewing our velocity prediction for this boat, I would expect the increase in boatspeed (from poled-out jib to symmetric spinnaker) to be 10-12% in 5-10 knots of wind, decreasing to 7% in 15-20 knots of wind – a bit more than you have recorded, possibly due to the difficulty of keeping the spinnaker full. The relative speed differences should reduce in stronger winds.’

THANKS

To Craig Nutter for his help on the day. A veteran of two America’s Cups and a Whitbread Race, Craig is now manager of the Medina Yard in Cowes and a good friend of YM.

Tel: 01983 203872

Email: info@medinayard.co.uk

Web: www.medinayard.co.uk

THANKS

To Sunsail for loaning us three F40s. Sunsail is an approved RYA Training Centre offering a comprehensive range of RYA theory and practical courses, from Start Yacht to Yachtmaster, and race training courses, including spinnaker handling. Friendly, experienced instructors can even provide one-on-one training on your own yacht.

Tel: 02392 222221

Email: sailing.schools@sunsail.com

Web: www.sunsail.co.uk